Bunraku is a form of traditional Japanese puppet theatre founded in 1684. Its style had developed and finally completed in the 1730s. The plays have been performed exactly in the same way since then. Because of this long tradition, bunraku was designated as the Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2009. This unique Japanese theatre reveals totally different meanings to today's audience especially when it is seen from the Western theatrical point of view. Referring to Donald Keene, Roland Barthes, and Susan Sontag, this paper explores how a bunraku play is constructed with various audio and visual elements and analyzes how the audience perceptually recomposes them into a play and appreciates it.

|

| Various hand props |

On the other hand, bunraku also constantly reminds the audience that it is only a show. During the play, the audience is forced to ignore the existence of three puppeteers that manipulate a puppet even though they are on the same stage. They do not try to hide themselves from the audience at all. The head puppeteer even shows his face to the audience. The interesting point here is that they are seen as if they were just standing next to or behind the puppet. They do not seem to manipulate it since their hands are completely covered with its cloth. They are there as if they observe it closely together with the audience. The head puppeteer does not show any emotion at all on his face during the play. He just stares at the puppet. The other two faces are covered with black cloths so that the audience would not know how they look. For the audience, the puppeteers and the puppet are seen as separated beings although they are actually united and one controls the other. As a result, the exposure of the puppeteers on stage makes the puppet look more independent rather than dependent.

What drives the audience to read the movements and gestures of a puppet is a chanter's narrative heard simultaneously all through the play. The chanter sits on a sub stage set next to a main stage. He only narrates, sometimes as if he sings. Not only does he tell the story to the audience, but also he describes each scene, suggests what characters think, and impersonates all the characters by himself. He chants very emotionally, sometimes with loud voice, whispers, and gasps. His narrative is much exaggerated and rhythmically stressed by a shamisen player's beats. Because his narrative flows very smoothly, dialogue and description parts are not obviously separated. He even has rich facial expressions and gestures while he is narrating, but again the audience is forced to ignore his existence and the shamisen player on the sub stage. The puppets on the main stage are to be focused all through the play. What the audience needs during the play is just the chanter's narrative and shamisen player's music. The audience's eyes are fixed to the main stage while listening to them. Barthes calls this integrated theatrical experience as "a total spectacle but a divided one" (Barthes 55). Sontag further says that bunraku "isolates – decomposes, illustrates, transcends, intensifies – what acting is" (Sontag 2). This point is also argued in the context of a German playwright Bertolt Brecht's Verfremdungseffekt (distancing effect) in his performing-art theory (Skipitares 13).

|

| Chanter and shamisen player |

Story lines and themes of bunraku are also well-structured for the audience to have unique theatrical experience. Most bunraku stories deal with serious issues that relate to farewell and death, which are the common themes often seen in the famous bunraku playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon's double suicide stories. Usually the story is about heartbreaking farewell to a loved one. They can be lovers, a husband and wife, siblings, or parents and their child. On stage, a chanter's voice by the chanter and shamisen sound function very well to dramatize this kind of tragedy. In many cases, the story starts with the violation of an ordinance or a norm regarding money, honor, or love. The main characters are usually outcast or fleeing from the community where they once belonged. Their conflicts with the society and dilemma push them to the final solution, a suicide. Their obligations (giri) and feelings (ninjo) continuously conflict with each other in their hearts. In many cases, this storyline seemed convincing for the audience at the time probably because of their Buddhist belief was widespread spread then. When the main character says to the loved one that they will be together in the next life, they both believe in reincarnation. According to Keene, bunraku plays had been very successful because the stories were basically romantic. He says that the audience had no chance to demonstrate their loyalty in their real lives and found satisfaction with the characters in the bunraku plays, which is almost same as ordinary American people who feel a sense of identification with the heroes in the Western movies (Keene 145).

|

| Bunraku stage |

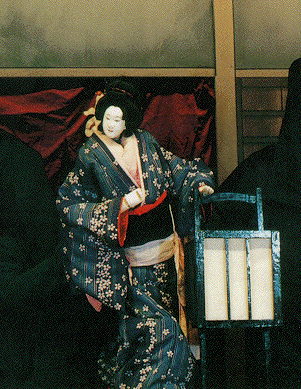

Bunraku is far from realism. The puppets do not have rich expressions on their faces. They do not overact, either. Their hands and feet are not crafted elaborately enough for that. On the other hand, the way chanter narrates is much exaggerated and formalized. According to Keene, bunraku does not focus on realism at all from the beginning. Chikamatsu, who is considered the best bunraku playwright in history, once wrote that art lay in the narrow area between fiction and realism (Keene 125). He also said these two should not be off balance in the play. Here the term 'realism' does not refer to the visual and audio verisimilitudes of the characters, but to the movement and gestures of a puppet that triggers deep emotion in the audience. This is what Barthes calls "sensuous abstraction" that includes "fragility, discretion, sumptuousness, unheard-of nuance ... impassivity, clarity, agility, subtlety" (Barthes 60). He further points out that this fetishism of the body's gestures decomposes the totality of a human actor and the body's organic unity in the Western theatre (Barthes 59). In bunraku, the concepts of fiction and realism had evolved into two technical terms: furi and kata. Furi refers to basic human movements in the play such as sitting, running, and crying. These are all formalized and presented in the same ways each time they are performed. Kata is a pose that shows the beauty of a female puppet (e.g. the waving lines of the hems of kimono as seen from behind) or an intense emotion of a male puppet. Kata is also stylized, but the audience finds real beauty in it. According to Keene, kata has no direct connection with the text at all. He says that besides psychologically interpreting a character in the play, a puppeteer's main purpose is to show the audience the moment of visual beauty that he reads and senses in the text (Keene 168). Here the audience anticipates the moment of human beauty created by the inanimate puppet.

Bunraku has been considered a part of Japanese traditional theatre for a long time. However, when it is examined from the Western point of view, it surely shows new aspects to today's audience although the stories and the language used in the plays are very old. Its theatrical experience also decomposes the concept of the Western theatre to a certain degree and makes us think what acting is. Realism in bunraku is sought not in the verisimilitudes of the characters but in the movements and gestures to which the puppets allude. This art of allusion also suggests that the practice of reading emotions in an inanimate bunraku puppets might have laid the foundation of today's Japanese character-loving culture.

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿