The following article was written as an assignment for the Classical Japanese Cinema class.

|

| Good Morning |

Good Morning (Ohayo) is

Ozu Yasujiro's second color film made in 1959 nearly at the end of his career. He is also credited as the scriptwriter in this film with

Noda Kogo. In 1983, a critic/scholar of French literature

Hasumi Shigehiko wrote a book about him and his films. Unlike the title Director Ozu Yasujiro which sounds like a biography of Ozu, what Hasumi actually did in the book was to trace the thematic elements in detail in all the Ozu films and find out the new characteristic of the films that had never been pointed out before. Unfortunately, although Hasumi occasionally refers to the film title, he does not write much about

Good Morning in his book. In this paper, I would like to analyze the narrative structure of

Good Morning more in detail using Hasumi's and

Roland Barthes' theoretical terms of narratology, and illustrate the rich narratological structure of the film.

|

| Director Ozu Yasujiro |

Before exploring the film, I would like to briefly explain what Hasumi actually sees in Ozu's films and what kind of concepts he uses in his analysis. He avoids going into auteurism and analyzes the films based on his “film experience” in order to “touch cinema in its rawness.” More specifically, he says that it is to notice several elements that co-exist and become pluralized at the same time on a segment of the film, which thus form the rich significative field on the screen. According to him, the beauty of Ozu's films lie in these co-existence of multiple stories. To illustrate his point, Hasumi uses two terms: a narratological structure and a thematic system. The former is not “the stories that link the scenes in individual works,” but “the synthesizing force that fuses the oppositional and heterogeneous into a single unity without excluding anything.” The latter term is, on the other hand, defined as “the expressions in significant detail that transcend the successive chain of sequences and intersect with each other in the realm that is different from the chronological order.” These two terms are mainly applied to analyze Ozu's films in his book.

|

| Roland Barthes |

I would also like to define two more narratological terms that are to be used in my analysis since Hasumi's two terms mentioned above are not enough for a single film analysis. One of them is what Barthes calls “the mainspring of the narrative activity” or “logical time,” which “prevail [...]the apparent fracturing of units being still closely subordinated to the logic which binds together the nuclei of the sequence.” In a film, a story unfolds with the function of narrative. Suspense and mystery are the perfect examples of this. As we will see the examples later in the film, they are “a way of gambling with structure, with the ultimate goal being, as it were, to risk and to glorify the structure. Hasumi uses the term “narratological sustention, in the similar way. The other technical term I would like to use is ‘discourse' in the film. This simply means the topics the characters in the film talk about. At least these four terms need to be clarified before analyzing the film.

|

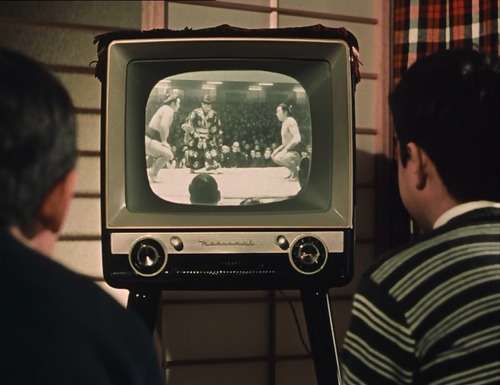

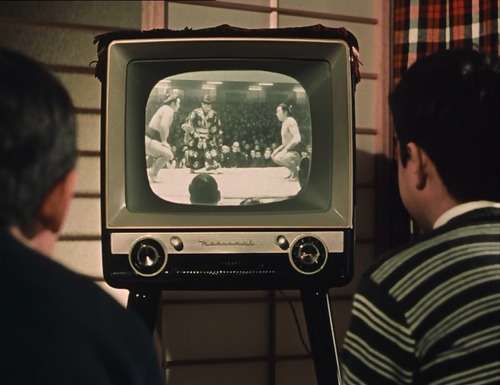

| A scene from Good Morning |

As Hasumi points out as the general characteristic of Ozu's films,

Good Morning does not have dramatic elements in the story. Only daily lives of six lower middle-class families living in Kawasaki in the late 1950s are depicted in detail. Daily situations including going to school, sewing at home, and drinking at a bar are repeatedly depicted in the film. There are a few, small mysteries for the spectators that develop the story such as missing of a collected due among the wives. This mystery is, however, to be solved soon within ten minutes in the film. There are some other small mysteries for each character (e.g. Harada's wife does not know why Hayashi's children do not talk to her), but they are not shown as a mystery at all for the spectators since the reasons are shown earlier in the film. There is also a little adventure of a boy Zenichi who tries to escape from his room to the neighbor house to watch TV, but still it shortly ends. All the mysteries and adventure in the film do not have enough length and strength to draw the spectators' interest toward the resolution. Comparatively the most dramatic events in the film are the disappearance of two Hayashi's brothers Makoto and Isamu, and the day of a new TV set coming to their house that both occur at the end. These events are received as a surprise for the spectators simply because how the characters came to the consequence are not shown in the film at all. The questions of where to go by the two brothers and what to buy from a home-electronics salesperson next door by their parents are being suspended in the film for a while until the end. In this way, these seemingly small and less-dramatic events are shown with more surprise to the audience.

|

| A scene from Good Morning |

What is shown instead of mystery and adventure in the film is the conflicts and reconciliation among the members of six families living in a small neighborhood. Their interwoven relationships between each other are gradually introduced to the spectators with the topics they talk about. Taking a pumice stone and farting are the topics that are talked about among the children, Heiichiro (their English teacher), and Tomizawa's husband in the different place and time. A TV issue is discussed in more groups among the children and mothers at their houses, and the fathers at the bar. A retirement issue discussed in the bar is later raised again at Hayashis. All these discourses spreading among the characters rarely unfold the story, but show the relationships between them and set the characteristic of each character. This can be only done with the situation that the telephone was not available at home so that people had to convey their messages by word of mouth (In Japan, a telephone became available at home in the 1970s). Sometimes a topic is discussed so intensively that the characters are caught up by it. The discourse of unnecessary greetings made by adults, which Minoru brings up in criticizing the way adults greet each other, is a typical example of it. The discussion over the issue actually put Minoru and Isamu into the battle with their parents and Heiichiro to reveal his hidden intimate feeling for Setsuko to his sister.

|

| A scene from Good Morning |

The narratological structure that Hasumi sees in Ozu's films can be found in the conflict and reconciliation that the discourse creates among the characters. The spectators finally know the conflict that the brothers had with others has been dissolved by seeing them saying “Good morning” to their parents and neighbors. This “movement towards the unification of oppositions” is what Hasumi calls “the true narrative of Ozu.” These conflict and reconciliation process can also be seen among the other characters. For example, two different salesmen visit the families while the wives are at home. The hard-sell salesman visits each house first and does coercive sales to the wives. After a while, the other gentle-looking salesman comes to each door and tries to sell them an emergency bell that can scare the hard-sell salesmen away. The later scene at the bar shows that the two salesmen actually worked as a pair and the first one threatened the wives so that they are more likely to buy the emergency bell from the second salesman. The point is that both drink at the same small bar with the wives' husbands. In there, they are depicted as the workers who finish their work at the end of the day and are having a drink. Here the conflict between the wives and salesmen is canceled out and neutralized. The first characteristic of the salesmen are changed and the conflict no longer exists. Such “unifying movements through sites of co-existence, where affirmed together” is the Ozu's “narratological structure” that can be also found in

Good Morning.

|

| A scene from Good Morning |

What Hasumi sees as another beautiful characteristic of Ozu's films, which he describes as “the thematic systems,” can be found in the juxtaposition of the characters in the film. According to him, something new starts when two intimate characters stand next to each other and look at the same object in the same direction in Ozu's films. At this moment, without seeing each other and saying anything, they show a sympathetic feeling shared between them. This is what he calls the “Ozu's lyricism” and it is sometimes enough to show it just to repeat the other's gesture. These scenes can be found at the end of

Good Morning when Heiichiro and Setsuko are standing next to each other at a platform and looking at clouds in the sky. While waiting for a train, they both look at the clouds and talk to each other. What is actually done here is that Setsuko just repeats what Heiichiro says about the weather and the shapes of the clouds they are looking at. The spectators definitely see their intimate feelings toward each other and notice the beginning of their new relationship in the near future. This is a perfect example of juxtaposition that clearly characterizes Ozu's films.

|

| Ozu Yasujiro |

What Hasumi calls as “the excessive details” that inevitably draw the spectator's attention, however, can only be pointed out when they are compared with other Ozu's films and found the similarity between them. The element that the spectators surely notice in

Good Morning is the “strange space” that emerges when the two characters face to each other without catching each other's eyes. Ignoring the principle of imaginary line is often referred to as one of Ozu's cinematic characteristics. Hasumi says that their gazes do not seem to meet but pass parallel to each other. He also points out that Ozu did not pay any attention to the principle and instead interprets it as a cinematic effect that the spectators may become uneasy when they see the character in the film looks like staring at them. According to him, that's when they have a sense of urgency that the film is no longer considered as a film. This moment of breaking ‘the forth wall' by the character's gaze often appears in

Good Morning. If examined more in detail, however, most characters' gazes do not go straight to the spectators' eyes outside of the screen. In many cases, they look slightly up or down toward the camera. Sometimes they look straight to it, but it is obvious from the context that they are talking to the person in front of them in the film and is more natural for the spectators to regard the scene as so. Hasumi also points out that Japanese do not look into other's eyes as often and relentless as the characters do in Ozu's films, but at least most characters in

Good Morning actually avert their gazes within a few seconds.

|

| A scene from Good Morning |

What may make the spectators more uneasy in the film instead is that the character does not say anything and just acts even though no one in the world of the film watches his act. The little brother Isamu is the one who does this incomprehensible action. In the middle of the film after Okubo's husband showed up at the entrance of Hayashi's house by mistake and left, the boy, who is going back to his room on the hall way, suddenly turns to the camera and pumps his fists into the air as if he had fought with the intruder and defended his family. He then walks a half way through, but again suddenly turns to the camera jumping and spreading his arms wide. He looks very cute and his inarticulate excitement is adequately expressed in this scene, but the question about whom he acted for may remain in the spectators' minds. Since his mother has already gone to the kitchen, there is no one to watch his acts in the hall way. The scene is hard for the spectators to interpret. They may laugh at the boy's cute action and may not think much about what his acts were for. This can be called as the moment when the film no longer presents the fictional world in a film and the character directly tries to interact with the spectators, which may expose the limit of a film to them as Hasumi suggests.

As discussed above, all the characters are intricately arranged in the film in order to show the relations to each other in detail through different kinds of discourses they share. Dramatic elements that drive the story to develop are rarely used here. Instead, the spectators may encounter the uneasy moment that may break the rules of cinema and force them to realize their own act of watching the film. With the help of Hasumi's postmodern cinema analysis, we can still take a various hermeneutic approaches to the film and find rich meanings in “the excessive details” of Ozu's films even in the present time after they were produced more than 50 years ago.

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿